Middle Ground

Dann Nardi: Dichotomies, Differences, and in Between… by Buzz Spector

Characterized by a subtle elegance of materiality and form, Dann Nardi’s sculpture resonates at second glance. Using commonplace materials deployed in a simple structural syntax, Nardi’s work doesn’t scream for our attention, but viewers receptive to its quietude encounter an art of elemental dignity and unexpected emotional impact.

The industrial and architectural references in Nard’s art would seem to ally it to the Minimalist work of Richard Serra or the late Donald Judd. But Nardi is less interested in rigorous intellectual systems than in the ways his sculptural practices may instigate visual pleasure. His art shows considerable awareness of critical-theatrical discourse, but its main purpose isn’t to illustrate that discourse. In a recent interview, the artist emphasized the nature of this distinction: “I don’t see [my work] as intellectualized, but it is smart work.” Nardi’s work employs dichotomies of form and structure – inside, outside; lightness, heaviness; and indeed, light, dark – that comment, through the technical ironies of their utilization, on a range of social circumstances whose existential proportions could be seen as similar to those of the sculpture.

Middle Ground, Nardi’s exhibition at the Illinois State University Galleries, is a project in two parts. One component is a survey of the artist’s public art commissions and related outdoor works, documented through photographs, drawings, maquettes, and text. The other part of the exhibit is a site-specific installation that summarizes Nardi’s artistic and philosophical concerns to date.

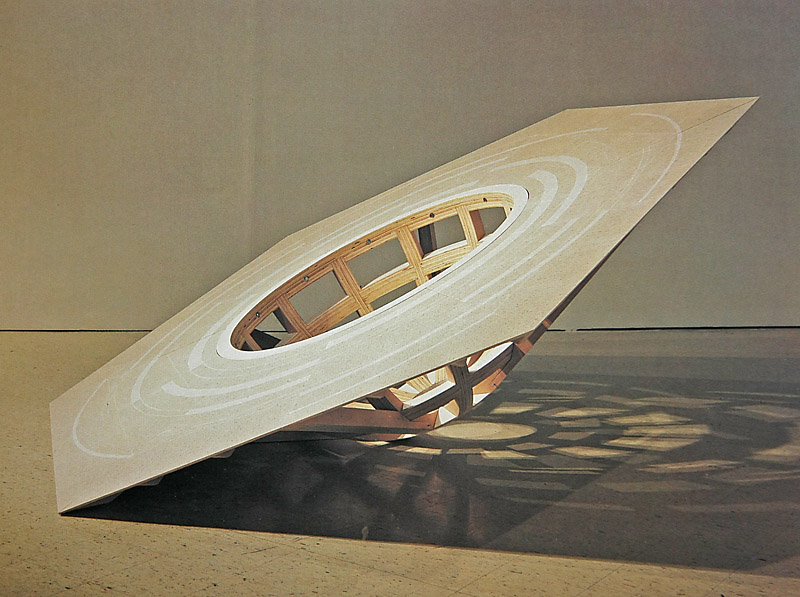

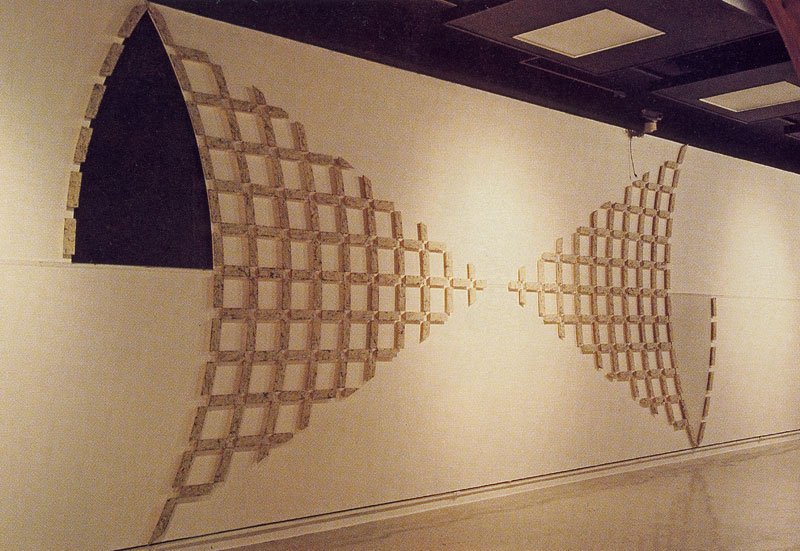

With a few alterations to the interior architecture, Nardi has affected a dramatic transformation of the main gallery. Viewers entering the room encounter a row of four columnar shapes, rising to the ceiling, positioned parallel to the left hand wall. To the right, on the floor near the partition enclosing the artist’s public art project documentation, is a large, basin-like form in wood, resting on one side of its wide hexagonal rim. Also to the right, near the rear gallery wall is an upwardly spiraling wooden staircase form whose traylike risers are filled with fertile black soil. A facade, mounted on three of the gallery walls, includes cutout shapes that trace the outlines of Nardi’s other gallery elements. But the least obtrusive component of the installation may be its most important aspect: a two-inch wide “shelf” of plexiglas, mounted by one edge and slightly above eye-level, that runs the perimeter of the gallery. The clear plastic strip is mounted so that the words of the text printed by hand in black ink into its surface can be read by the shadows they cast on the wall below.

Beginning as if in the middle of a sentence, the words Nardi has written for Middle Ground comprise a poetic narrative of the experiences and values that shape the artist’s personal vision. Nardi’s absorption with “the gray area,” that is, the spaces between ideas and things, is emphasized here by his use of cast shadows to make his text decipherable. The endlessness of the text is reiterated in its final works, combining a line from a Peter Gabriel song, “and we end as we began,” with the phrase “you are here… you are…you,” repeated in various languages until the letter forms themselves dissolve into a sequence of fragmentary lines.

Nardi spent several summers in his youth digging graves in a cemetery and that experience is also noted: “I thought about the surface of the earth…its plane, the line of division between two worlds, two realities.” In addition to these life and death allusions, we find an artworld reference, to Michael Heizer’s earthwork, Double Negative, 1970. Heizer’s twin gigantic excavations, cut across the bed of a ravine in the southern Utah desert, have eroded considerably in the 25 years since the work’s execution and, in a gravediggers view of Minimalism, may be likened to a pair of tombs filling themselves in under the annihilating action of time.

Nardi’s humane social consciousness can be seen throughout the installation. For example, he describes the row of column-forms in Middle Ground as the “Four Brothers,” and indeed, the arrangement of hollow forms, opening as they ascend, may be read in a communal sense.

The four hollow elements are each mounted beneath a ceiling light fixture, so that light emerges from many apertures in the surfaces of the forms. The first element, covered in an emulsion of sawdust and glue on wire mesh, glows with membraneous translucency. The second, a lattice of white painted wood, has the same armature as that supporting the other elements and, without a “skin,” reads as an almost skeletal apparition. The third, covered in laminated and black painted plywood, conveys a sense of interior density, which only a close look reveals to be illusory. And the fourth, clad in red stained cedar shingles, seems as woody as a great inverted tree trunk. The societal resonances in this chromatic arrangement are easily inferred.

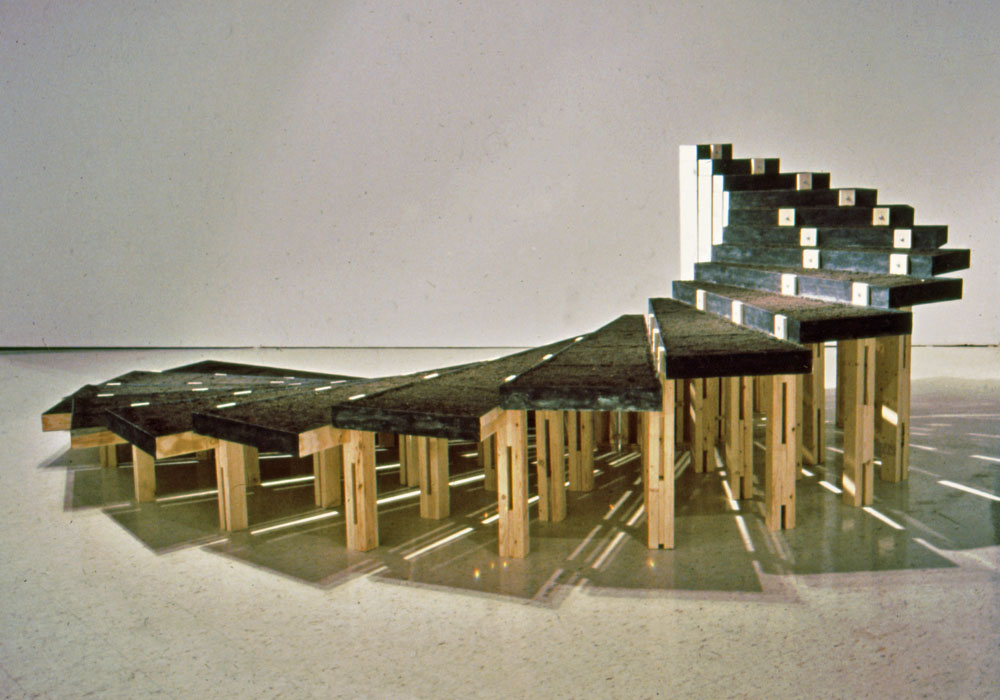

The large hexagonal piece also has a provisional title, “In the Balance,” and it reads as if it were tipped over. The exposed armature allows the viewer to see an otherwise invisible interior space, for which the mind provides the (en)closure. The dirt-filled stairway, which Nardi calls “Rise and Fall,” expresses another order of dichotomy, that of fecundity/sterility is that rich dark loam ready for planting or is it barren ground?

Questions abound as we move through Middle Ground, yet it is the nature of Nardi’s art to raise more questions that it answers. The artist’s generous responsiveness to site is articulated in his installation’s eloquent proportions, but his expansive liberalism is recognized in the allusiveness of his materials and forms. Nardi isn’t seeking the safety of a conformist middle at all. Rather, he quests for a more problematic “between” reminiscent of T.S. Eliot’s great lines from “The Hollow Men”:

between/the conception/and the creation/falls the shadow/

between/the emotion/and the response/falls the shadow

Perhaps Nardi’s dichotomy reads “between the sculpture and the culture fall a shadow.’